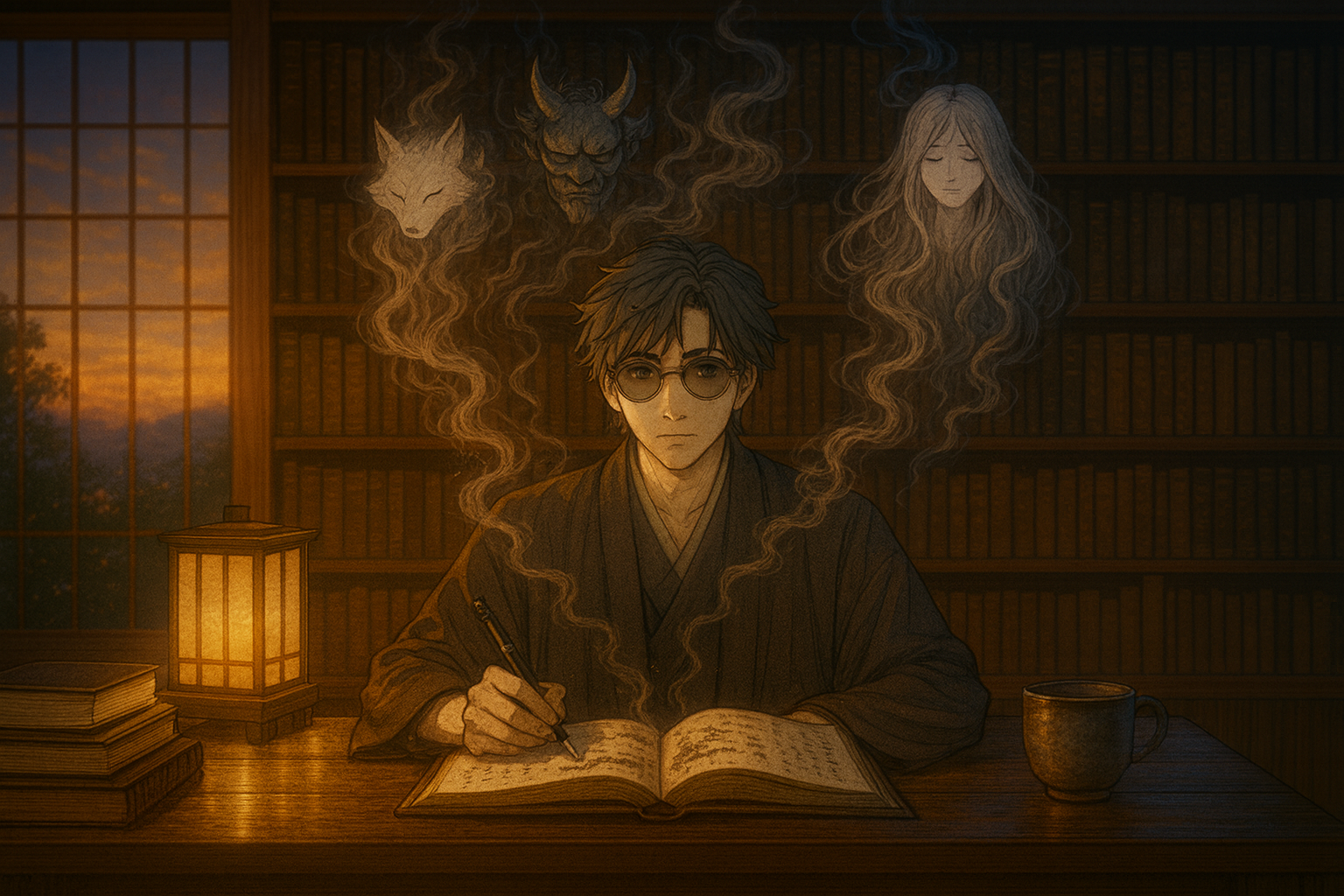

Japanese yokai—fox spirits, oni, yuki-onna, and many more—are not just “monsters.”

They are mirrors of human fear, desire, humor, and loneliness. That is why they make such powerful material for short stories.

In this guide, we will look at how to turn yokai into original short fiction: from choosing a yokai and researching folklore, to building characters, settings, and structure. You can use these steps whether you write in English, Japanese, or a mix of both.

1. Understand What Yokai Really Are

Before writing, it helps to shift your image of yokai from “scary creature” to “symbol.”

- Yokai reflect emotions and social rules.

For example, a fox (kitsune) can represent seduction, trickery, or wisdom; a yuki-onna can represent cold beauty, betrayal, or mercy. - Many yokai are shaped by place.

Mountain spirits, river gods, and town ghosts each carry the atmosphere of their environment. - Yokai are flexible.

The same yokai can be terrifying in one story and heartwarming in another.

When you pick a yokai, ask: What human fear, desire, or wound does this creature represent for me?

2. Choose One Yokai and a Core Theme

Trying to use too many yokai at once can weaken a short story. Start small:

- Pick one main yokai (for example: kitsune, tengu, rokurokubi, zashiki-warashi).

- Decide the core theme you want to explore. Examples:

- Trust and betrayal

- Freedom vs. duty

- Loneliness and connection

- Tradition vs. technology

Then combine them into a simple concept:

“A lonely office worker meets a modern kitsune who offers him a life without responsibilities.”

“A yuki-onna running a small café in a snowy town tries to forget her past as a man-killing spirit.”

This “yokai + theme” pair becomes the backbone of your story.

3. Research Folklore—But Don’t Just Copy

A little research protects your story from stereotypes and makes it richer.

- Read one or two reliable summaries of the yokai’s legends.

- Note typical traits: appearance, powers, weaknesses, usual locations.

- Look for less common versions of the story. Sometimes regional variations are more interesting than the most famous one.

Then, instead of copying an existing tale, twist it:

- Change the era (Edo → near future Tokyo).

- Change the point of view (tell the story from the yokai’s side).

- Ask “What if this legend continued into the present day?”

Respect the spirit of the folklore, but let yourself play.

4. Turn the Yokai into a Character, Not Just a Monster

Great short stories are driven by character, not just concept.

Give your yokai:

- A clear desire.

What do they want right now? Revenge, love, a friend, silence, fun, worship, escape? - A contradiction.

Maybe an oni who hates violence, or a kitsune who is bad at lying. - A human-like weakness.

Jealousy, laziness, fear of abandonment, hunger for recognition.

Also think about their human disguise: name, clothes, speech style, job.

The more specific they become, the easier it is to write natural scenes.

5. Build a Setting That Echoes the Yokai

Setting and yokai should reflect each other.

- A kappa might appear near suburban rivers, abandoned water parks, or storm drains.

- A tengu could show up around mountain shrines, climbing trails, or deserted ropeways.

- A traditional zashiki-warashi fits in old houses, empty guest rooms, or countryside inns.

Use small sensory details to create atmosphere:

- Sound: crows, cicadas, distant festival music, train crossings

- Smell: tatami mats, incense, rain on asphalt, yakitori smoke

- Light: lantern glow, neon signs, foggy moonlight, vending-machine blue

These details make the yokai feel at home in the world.

6. Decide the Tone: Horror, Comedy, or Something Between

Yokai stories don’t have to be pure horror.

- Horror: emphasize silence, shadows, and the unknown. Hide the yokai for as long as possible.

- Dark comedy: exaggerate the yokai’s quirks (a perfectionist oni, a lazy death god).

- Heartwarming / bittersweet: show the yokai struggling with human emotions they don’t fully understand.

Pick one main tone and let it guide your word choice, pacing, and ending.

7. Use a Simple Short Story Structure

You don’t need a complicated plot. A compact structure is enough:

- Hook (Opening)

Show the protagonist’s everyday life and hint that something is “off”: a strange rumor, an odd customer, footsteps on the roof. - Encounter (Middle)

The protagonist meets the yokai, or strange events escalate. Secrets are revealed; the theme (trust, loneliness, etc.) becomes clear. - Choice and Change (Climax & Ending)

The protagonist must make a decision influenced by the yokai: accept a deal, break a taboo, let go of someone, protect or betray.

Show how this choice changes both the human and the yokai, even in a small way.

Keep scenes focused. In a short story, every line should push character or theme forward.

8. Add Japanese Cultural Details Carefully

Cultural details are powerful, but they should serve the story:

- Use specific objects: ema (votive plaques), omamori, festival masks, senbei, kotatsu.

- Use social behavior: bowing, honorific speech, senpai–kohai dynamics, family expectations.

- Avoid long info-dumps. Instead, show how characters naturally interact with these elements.

If you write for overseas readers, you can sprinkle a few Japanese words and explain them briefly through context:

“She placed the omamori—a small cloth talisman from the shrine—on the counter.”

9. Balance Japanese Terms and Readability

Too many romaji words can exhaust readers; too few can weaken the flavor.

- Use Japanese terms for key cultural items or concepts.

- Keep sentence structure clear and simple, especially if your audience includes language learners.

- Consider adding a short glossary at the end for important words like “yokai,” “kitsune,” or “miko.”

Your goal is not to show off vocabulary, but to invite the reader into your world.

10. Revise with Feedback (Including AI)

First drafts are often messy. That’s normal.

When revising:

- Check if the theme is visible from beginning to end.

- See whether the yokai feels like a real character, not just a jump scare.

- Read dialogue aloud to check rhythm and personality.

- Use AI tools to suggest alternative phrasing, grammar fixes, or title ideas—but always make the final decisions yourself.

11. Three Yokai Story Seeds You Can Try

You can use these as prompts for your own short stories:

- The Convenience-Store Oni

An overworked oni hides his horns and works night shifts at a convenience store. One day, another yokai recognizes him and forces him to choose between his peaceful human life and his violent past. - The Fox Who Forgot How to Lie

A kitsune wakes up with no memory and discovers they can no longer lie. They must help a human solve a problem honestly—or disappear. - Snow Woman’s Summer

A yuki-onna rents a small room in a seaside town to escape the mountains’ bloody memories. But the heat weakens her powers, and she must decide whether to save a drowning child even if it means melting away.

12. Related Articles (Internal Links)

To deepen your understanding of yokai and Japanese-style storytelling, you can also read: